GME DVD Distribution – The Seasons (1968-1971), Marcel Hanoun’s Cinematic Quadriptych, Now Available for Institutional Sales

/GME is pleased to present a DVD boxed set (publlshed by Re:Voir) of Marcel Hanoun’s THE SEASONS (LES SAISONS). This film is a quadriptych, which includes L’ÉTÉ (1968), L’HIVER (1969), LE PRINTEMPS (1970), and L’AUTOMNE (1971). The DVD boxed set also includes a 100-page booklet about each of the films, and also includes an interview with the filmmaker. This publication thematically complements another film about the four seasons, Henri Storck’s SYMPHONIE PAYSANNE (1942-1944), that is also available from GME.

“Hanoun was born into a Jewish-Algerian family in Tunis in 1929, when Tunisia was still a French protectorate. Escaping the worst of World War II, he came to Paris to stay after the Liberation, and worked there as a journalist and a photographer. (His father had been an avid amateur camera buff, influencing his son’s vocation.) Hanoun directed his first film for television in 1956, about refugees from that year’s Soviet-suppressed Hungarian Uprising. This was also the year of Bresson’s A MAN ESCAPED (1956), a film which was a revelation to the young Hanoun—and the inextricable ideas of displacement and freedom would be key to the future work of this self-styled Wandering Jew. Like Bresson, Hanoun the filmmaker would be a theoretician as well as practitioner, his films the conscious workings-through of his ideas about cinema. To the end of his life he continued to write copiously, and even edited two revues: First Cinéthique, which began its brief run in 1969, and then Change cinema, in 1977.”

– Nick Pinkerton, Artforum

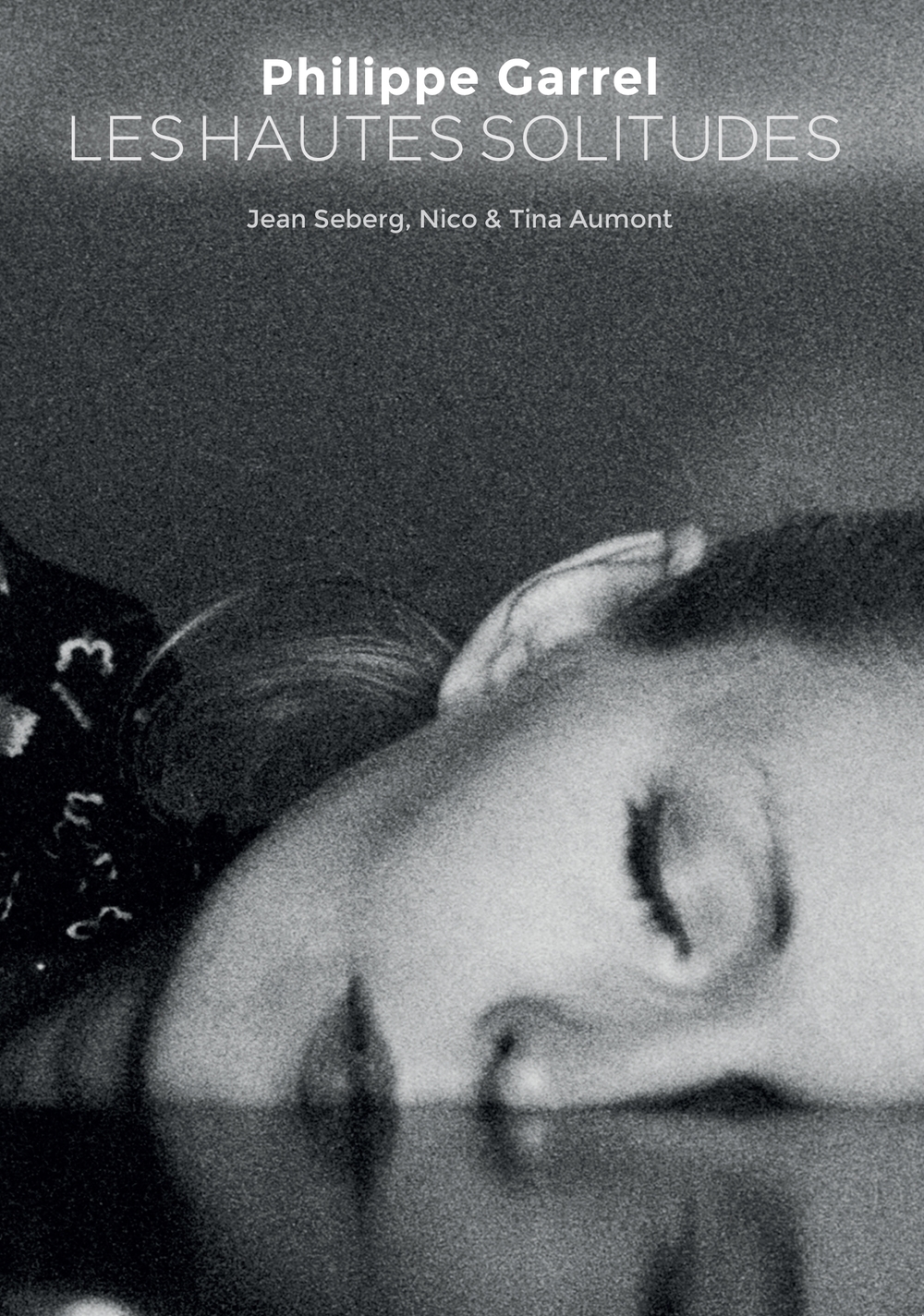

His first feature film, UNE SIMPLE HISTOIRE (1959), showed at the Cannes Film Festival alongside Truffaut’s THE 400 BLOWS (1959) and Alain Renais’s HIROSHIMA MON AMOUR (1959). However, after the success of this film, Hanoun struck out in a more independent direction, and employed a more minimalist approach to his filmmaking. Historically, he now represents a bridge between the filmmakers of the French New Wave and the generation that followed (Jean Eustache, Maurice Pialet, and Phillippe Garrel (LE REVELATEUR, 1968; LE LIT DE LA VIERGE, 1969; LES HAUTES SOLITUDES, 1974).

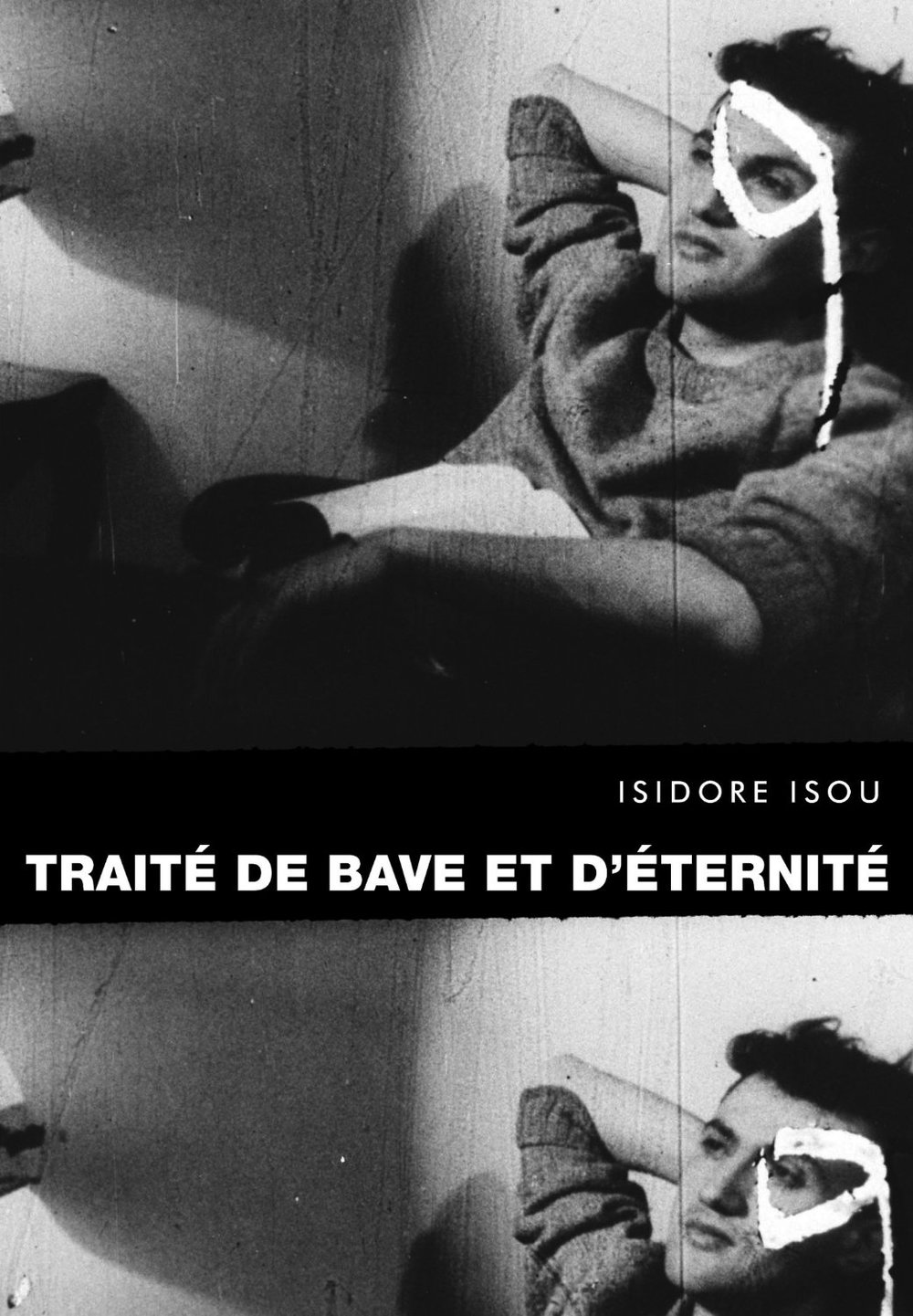

“Hanoun theorized a cinema in which the word and image were separated and given equal value. In this, Hanoun was working along the same lines of thought as the radical experimental filmmaker Isidore Isou, whose TRAITÉ DE BAVE ET D'ETERNITÉ proceeded along a similar path, but with a much more violent approach…Hanoun employs a more quiet, contemplative style, using a static camera and images that force the viewer to concentrate on the most quotidian aspects of existence and to accentuate the dichotomy between sound and image which is implicit in all of cinema.”

– Wheeler Winston Dixon

In L’ETE (SUMMER, 1968), Hanoun's “May '68” film, an Italian woman stays at a friend's house in the countryside after having been witness to the havoc in Paris. We see her alone in a house, walking in a field, doing cartwheels in a bikini, walking some more, pondering her relationship, and looking at herself in photos taken on the streets of Paris where she is posed against political graffiti. She writes to a German friend (whom we see/hear reading the letters) and thinks of her ex-boyfriend (whom we see in flashbacks and photos – he is named “Jean-Luc.” A reference to Godard?).

Far from showing a series of dramatic actions, Hanoun focuses on the in-between moments in the life of his beautiful young protagonist. He plays with fragments of the scene, reframing the image, using frames (doors, windows, a mirror as a tableau vivant). All of this confronts the viewer with a sort of catalog of repetitive acts, where drama and character development are absent. Because of these distancing effects, Hanoun reveals the key, the meaning of his film: the confrontation, the controversial relation between desire and reality.

In L’HIVER (WINTER, 1970). Michael Lonsdale plays a filmmaker who can't get his film made. We watch he and his collaborator talk about what they'd like to do, see ravishing locations in Bruges, and witness the relationship between he and his wife unravel. Hanoun’s formal investigation of the fragment and the (almost subliminal) flash frame, of very slightly altered variations and repetitions, which he applies to situation as much as to dialogue (often repeated, either within the same shot or from a different angle) reveals something of the interiority of film, of its creator’s unconscious, which becomes that of his characters. This structural resemblance to a Russian nesting doll should not confuse..The more Hanoun compresses his dreams of dreams within dreams (films), the closer he gets to intimacy.

LE PRINTEMPS (SPRING, 1970) is replete with narrative incident and characters. Two plotlines are cut together: a fugitive from the police (Michael Lonsdale), whom we later learn murdered his wife, takes refuge in various parts of the countryside, while a young girl (Veronique Andries) who lives with her stern grandmother (who kills and skins a rabbit in real time on-camera) matures through the absorption of scary fairy tales, experiments with cursing and smoking, and the arrival of her first period.

All of Hanoun's visual devices are at play – flipping from b&w to color and back; making the camera into a presence in a room (it serves as a mirror for the characters, or a window); his obsession with the beauty of the countryside and its inherent menace.

In L’AUTOMNE (AUTUMN, 1972, filmmakers (a director, played by Lonsdale again, and his editor, played by an actress known simply as “Tamia”), stare into the camera because we, the audience, are the film they are watching on an editing machine. What Hanoun does to reinforce his concept is to turn off the visuals (a blank screen) whenever Lonsdale or Tamia turn off the editing machine. (At that point we listen to phone calls.) When they are not editing, but the machine is on, Hanoun plays with overdubs on the soundtrack, gives us all-too-brief glimpses of the characters' fantasies, and quick-cut sequences of the couple talking. Lonsdale talks about shooting home movies, and we then see what are clearly Hanoun's own movies of a family outing. At the film's end we see footage of autumn in the woods, first in real time, then as fast-forwarded through by an editing machine – then the "countershot," the editing machine itself. The filmmakers are evidently done with their project.

◊

Additional Related Films Available from GME: