ALPHAVILLE (France, 1965, Jean-Luc Godard)

/“For all its influence, ALPHAVILLE still looks and feels like no other movie. More than a prophecy, it is poetry.” —Bilge Ebiri, New York Magazine

Jean Luc-Godard’s ALPHAVILLE (1965) cleverly amalgamates the genres of dystopian science fiction and film noir. In Godard’s endless journey to subvert cinematic conventions and tropes, he took the archetype of the “male anti-hero” and transposed him into a sci-fi setting.

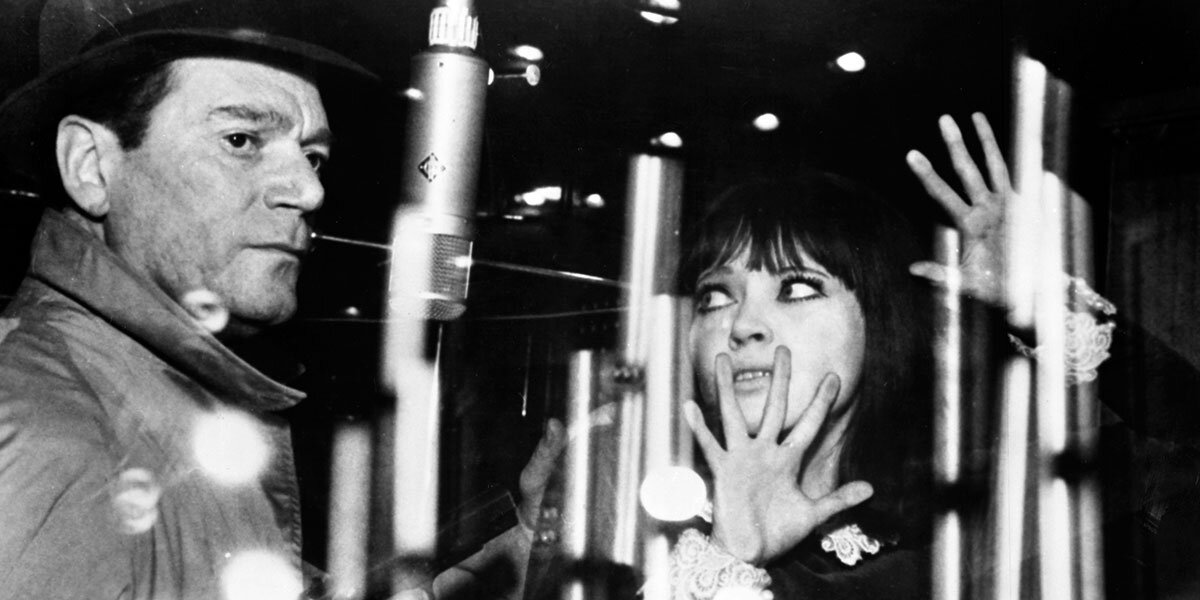

Secret agent Lemmy Caution (played by Eddie Constantine) is sent to the distant space city of Alphaville where he must track down and kill the inventor of the all-controlling computer Alpha 60. Imbued with shades of George Orwell, Alpha 60 has outlawed free thought and individualist concepts like love, poetry, and emotion. People who show signs of emotion are presumed to be acting illogically and are gathered up, interrogated, and executed. As a result, Alphaville has become an inhuman and alienated society.

Caution enlists the assistance of Natasha von Braun (played by the darkly luminous Anna Karina), a programmer of Alpha 60. Caution falls for Braun, and his affection introduces emotion and unpredictability into the city. Braun’s programmed responses slowly break down as the hardboiled detective introduces her to the concepts of “conscience” and “love” — words with which she is unfamiliar, since they have been progressively redacted from the dictionary of her father's totalitarian state. Godard ends the film on a note of romantic optimism, with Caution and Braun escaping their pursuers and a dying world, fleeing to safety through space (otherwise known as the Boulevard Périphérique) as Braun learns a new phrase: "Je vous aime.”

ALPHAVILLE is replete with gun-toting criminals, fisticuffs, and murder, recalling the classic gangster archetypes of American films noir (such as Ida Lupino’s THE HITCH-HIKER, Byron Haskins’ TOO LATE FOR TEARS, and Richard Fleisher’s TRAPPED) and even the French films noir of Jean-Pierre Melville (such as BOB LE FLAMBEUR) and Jacques Becker. As the archetypal American anti-hero private eye in a trench coat, Lemmy Caution’s old-fashioned machismo conflicts with the puritanical Alpha 60. This character was a hard-boiled FBI agent from English author Peter Cheyney’s series of detective novels in the 1930s and ‘40s. While never as popular in the United States, Lemmy Caution became something of a proto-James Bond film hero in France, with American expat Eddie Constantine portraying Caution in seven pulpy detective movies between 1953 and 1963.

Distinct from later science fiction films such as Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY (1968), George Lucas’ STAR WARS (1977), Ridley Scott’s BLADE RUNNER (1982), and the Wachowski’s THE MATRIX (1999), Godard brilliantly eschews futuristic sets and high-tech props for actual Paris locations in ALPHAVILLE. Paris in the 1960s was undergoing a dramatic architectural and economic transformation that would see the unprecedented redesign and reconstruction of entire districts. The last time the city had been subjected to such large-scale transformation in its built environment had been through Baron Hausmann’s mass urban plan in the 1850s and ‘60s, designed as much to prevent revolution and fire than for beautification.

Godard’s increasing fascination with Marxism and critical theory had given cinematic shape to his films as a form of social critique; they strove to express his anxieties about the creeping anonymity and alienation of an Americanized globalization. During the 1950s and ‘60s, as European economies were emerging from postwar austerity, De Gaulle’s then Minister of Culture, André Malraux, oversaw a vast project to “rehabilitate” the historic neighborhoods of the metropolitan center around Le Marais, which included the scrubbing and cleaning of facades and the transformation of residential buildings into office blocks and commercial units.

Low slung, classic edifices gave way to vertical skyscrapers of glass and steel, culminating in the Montparnasse Tower, which was completed in 1973. The price of land sky-rocketed, which served only to push the working and lower middle classes to the peripheries while depopulating the central arrondissements. This shift further entrenched income and housing inequality while celebrating a new global consumerism of elite, modern flats and domestic technologies. Released in 1965, Godard’s ALPHAVILLE positions itself at the epicenter of these socioeconomic changes.

The stark urban tonality of ALPHAVILLE is achieved in great part through noir-ish shadows created by cinematographer Raoul Coutard, whose black-and-white photography turns everyday objects and settings — exteriors of glass buildings, electronic doors, a hotel lobby, spiral staircases, a swimming pool, a room full of mainframe computers, a jukebox, a Kodak Instamatic — into the mise-en-scène of a convincingly dystopian world. Neon lights and brutalist architecture also lend a futuristic and otherworldly feel to ALPHAVILLE; this tone is also created by scenes projected in negative imagery. The lighting and positioning of Coutard’s camera often obscures the envelopes of buildings, thereby disorienting a sense of place. For instance, as Caution drives across a section of an industrial bridge alongside a passing train, the shot obscures the storied history and grandeur of Paris, transforming it instead into an industrialized landscape of a new architectural norm.

Now available from Gartenberg Media Enterprises in new 4K restoration produced by Studio Canal, Jean-Luc Godard’s ALPHAVILLE has never looked better.

ALPHAVILLE

(France, 1965)

Director: Jean-Luc Godard

Screenwriter: Jean-Luc Godard

Cinematographer: Raoul Coutard

Cast: Eddie Constantine, Anna Karina, Akim Tamiroff

- 99 minutes

- 35mm

- Black-and-white

- Sound

Distribution Format/s: DSL/Downloadable 4K .mp4 file on server

Published By: Kino Lorber

Institutional Price: $500

To order call: 212.280.8654 or click here for information on ordering by fax, e-mail or post.