The Film-Makers' Coop Will Host a 60th Anniversary Benefit Screening of Andy Warhol's SLEEP on December 1st and 2nd

/JOHN GIORNO IN ANDY WARHOL’S SLEEP (1963). SOURCE: IMDb.

Tonight, December 1st, and tomorrow, December 2nd, 2023, at 7pm, the Film-Makers’ Cooperative is hosting a benefit screening of Andy Warhol’s first major film, SLEEP (1963), at The Bunker at 222 Bowery. The Bunker was the long-term home of SLEEP’s star, famed poet and artist John Giorno, and the film will be shown on the occasion of its 60th anniversary.

In the mid-1980s, while working in the Museum of Modern Art’s Film Department, GME President Jon Gartenberg was instrumental in the resuscitation of Warhol’s films, like SLEEP, which were thought to be lost or destroyed after Warhol pulled them out of circulation. Gartenberg and Whitney Museum of Art curator John Hanhardt were integral to the “Andy Warhol Film Project,” an initiative to make Warhol’s films — with his permission — publicly accessible after years of obscurity.

Writing for the catalogue for the 1988 Warhol exhibition at the Whitney, Gartenberg noted: “this pioneering project forges a dynamic relationship between exhibition and preservation activities [and] creat[ed], for the first time, a well-documented foundation for the critical analysis of Warhol’s films, an analysis that can… be based on original sources and research materials which have been largely unavailable to historians, critics, and the general public.”

JON GARTENBERG AND JOHN HANHARDT EXAMINING A FILM IN THE WARHOL FILM COLLECTION, 1984. PHOTOGRAPH BY GEORGE HIROSE.

Writing for the recently released The Films of Andy Warhol Catalogue Raisonne (1963—1965), Hanhardt recalled:

[On] my first visit, in 1984, to a former Con Ed substation in Manhattan that had been turned into the offices for Interview and Warhol’s production company… I was accompanied… by Jon Gartenberg, then assistant curator in MoMA’s Department of Film, who would play an important part in establishing the process for the museum’s acquisition of the films. He had developed an expertise in handling avant-garde films, paying special attention to how artists treated celluloid and explored nonstandard uses of the medium. Gartenberg’s dedication to the artist’s intentions, rather than the industrial standards of commercial entertainment film, made him an ideal colleague in this initial examination of Warhol’s films… When we entered Warhol’s offices, we found numerous cans of film and boxes holding videotapes… [we] would go on to locate the ‘mother lode’ of Warhol films — both camera originals and projection prints — in a storage facility in Fort Lee, New Jersey, in August 1984…. In 1987, three years after Warhol agreed to release the films to the Whitney and MoMA, he died unexpectedly after surgery in a New York hospital.

In 2003, as part of a 75th Warhol birthday celebration organized by the Brooklyn Academy of Music, Gartenberg wrote:

My personal contact with Andy Warhol was fleeting, but my professional involvement with his cinematic creations was intimate… A mythology had already developed by the mid 1970s surrounding Warhol’s films, which by then had been withdrawn from circulation. Did they still exist, or did Warhol have them destroyed in one fell swoop? Because it was only possible to read about his films (in such books as Stephen Koch's STARGAZER), I was intent upon tracking down as many Warhol films as would surface in clandestine fashion [during my travels to Europe]… I still recall in vivid fashion the day when [John Hanhardt and I] retrieved Warhol's films from a remote storage facility in Fort Lee, New Jersey… It was an absolutely thrilling experience to project vintage prints of these films for the first time in twenty years. I was immediately struck by the extraordinary historical and artistic value of this body of Warhol films, which were produced over the course of five years… In terms of the sheer volume of films shot, the method of their production, the stable of actors and collaborators which Warhol employed, and the structural elegance of the films, Warhol’s cinematic output rivaled the productivity and complexity of D.W. Griffith's, who worked for five years (from 1908 to 1913) as a producer and director at the Biograph Company.

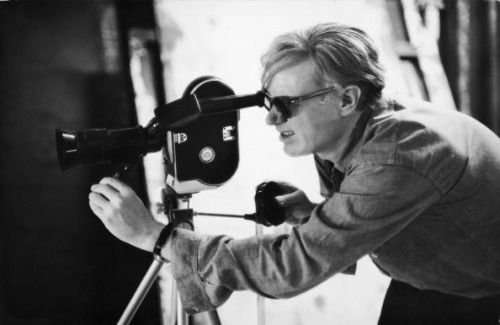

ANDY WARHOL FILMING ON A BOLEX, CIRCA 1960s. SOURCE: PINTEREST.