GME STREAMLINE PRESENTS THE SPANISH FILMS OF SEGUNDO DE CHOMÓN AND VAL DEL OMAR NOW AVAILABLE AS DIGITAL SITE LICENSES IN DVD/DSL BUNDLES

/GME Streamline is pleased to present digital publications of two under-recognized yet important Spanish cinema pioneers, Segundo de Chomón and José al del Omar, now available from GME as DVD/DSL bundles. Chomon was a rival of Georges Méliès, and cinema poet Val del Omar flourished during the Silver Age of Spanish Culture, alongside compatriot and friend Federico Garcia Lorca. Our objective in presenting these two monographic digital publications of these experimental pioneers of the moving image is to reposition them within the discourse of world cinema, rather than only to the confines of Spanish film history.

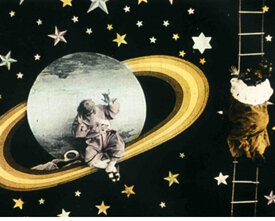

Segundo de Chomón is a key figure in the early years of cinema history, and one whose career has long been overshadowed by his French contemporary, Georges Méliès. The DVD collection SEGUNDO DE CHOMÓN (1903-1912): EL CINE DE LA FANTASIA presents 31 films by “the Spanish Méliès,” revealing a filmmaker of comparable imagination, yet unique artistry. This DVD is accompanied with a 111-page tri-lingual book containing an informative essay by historian Joan M. Minguet Batllori entitled “Segundo de Chomón: Beyond The Cinema of Attractions” as well as credits for each film and the participating archives involved in their restoration.

LES TULIPES (1907) LE SPECTRE ROUGE (1907)

Segundo de Chomón is, without a doubt, the most international Spanish filmmaker of the silent era at the same time as cinematic language hinted at its hegemony over other popular forms of entertainment, and which continued until the end of the silent era. Chomón worked continuously in two of European cinema’s most important production houses: Pathé Frères in Paris and Itala Films in Turin. He collaborated actively on some legendary films of the silent era, such as CABIRIA (1914) by Giovanni Pastone, and NAPOLÉON (1927) by Abel Gance. Most significantly, beyond the large-scale productions, his name is associated with a genre that is essential to understanding the history of the cinema of that time: trick films and fairy tales, i.e., those films that invited the spectator into a world of fascination.

The director’s wife, Julienne Mathieu most likely pushed him into movies. Mathieu had worked as an actress for the production companies Pathé and Méliès’ own Star Film. When her husband returned from a tour with the Spanish army in 1899, she brought him into contact with the emerging world of cinema. In 1902 he became a concessionary for Pathé in Barcelona, distributing its product in Spanish-speaking countries, and managing a factory for the colouring of Pathé films. For Chomón, this initially meant work as a colorist, tinting film by hand. It was a highly skilled and specialized trade that brought him good wages and steady work from Pathé which shipped films out to his studio in Barcelona. Chomón not only colored the film, he created subtitles and provided distribution to local theaters. He was so good at his job that a 1902 advertisement for BARBA AZUL (BLUEBEARD) promised “the finest example to be presented in Barcelona hand-tinted ex professo by the reputable film colorist Don Segundo de Chomón”—a commendation that’s especially noteworthy, as colorists were hardly considered star attractions at the time.

SUPERSTITION ANDALOUSE (1912) VOYAGE SUR JUPITER (1909)

Pathé clearly understood Chomón’s unique talents. He began shooting actuality films of Spanish locations for the company. In 1905, the company offered him a promotion in their main office in Paris, a job that would allow him to work consistently behind the camera. Chomón had directed movies before this move, but he would create his best-known work over the ensuing decade, including THE FROG and creative, futuristic shorts like A TRIP TO JUPITER and THE ELECTRIC HOTEL. The body of work he created over five years was outstanding. Films such as LE SPECTRE ROUGE, KIRIKI – ACROBATES JAPONAIS, LE VOLEUR INVISIBLE and UNE EXCURSION INCOHÉRENTE are among the most imaginative and technically accomplished of their era.

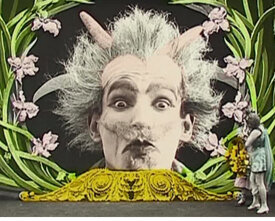

Chomón created fantastical narratives embellished with ingenious effects, gorgeous colour, innovative hand-drawn and puppet animation, tricks of the eye that surprise and delight, and startling turns of surreal imagination (see, for example, the worms that crawl out of a chocolate cake in UNE EXCURSION INCOHÉRENTE, one of a number of films where visitors or tourists are beset by nightmarish haunted buildings, a favourite de Chomón theme).

Chomón made sometimes nightmarish trick films that experimented with color and temporality, and would eventually influence the surrealist work of filmmakers Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí, making him, in many ways, the father of Spanish cinema. Buñuel and Dalí organized the first “cine-club,” or film society, in Madrid as college students in the 1920s, leaving little doubt about their familiarity with the internationally renowned Chomón, who was still making movies at the time. Buñuel, Dalí, and Chomón seemed to share a disregard for realism and conventional narrative form, surprising the viewer with unexpected images that could disrupt or disturb. It was their tableaus, more than their stories, that lingered.

SEGUNDO DE CHOMÓN

Born in 1904 at the time that Chomon’s films were emerging on the world stage, José Val del Omar’s filmmaking career began (ESTAMPAS, 1932) just a few years after Chomon’s ended (NAPOLÉON, 1927, Abel Gance). A believer in the cinema, Omar always was an early visionary, beginning with the projections being made when he was a child in the style of the magic lantern with candles and colored glass.

He was one of the most significant figures of Spanish avant-garde cinema, a contemporary and comrade of Federico García Lorca, Luis Cernuda, María Zambrano and other figures of the Silver Age of Spanish culture, interrupted by the Civil War, that formed the Generación del 36 (Generation of ’36). He was an accomplished creator -- poet, musician, researcher, inventor and proponent of cinema. He defined by himself as a cinemista, or cinema alchemist. (This is in parallel but distinct fashion to the trick films of Segundo do Chómon).

JOSÉ VAL DEL OMAR

The Deluxe Limited Edition boxed set VAL DEL OMAR: ELEMENTAL DE ESPAÑA is dedicated to the works of this unique solitary artist José Val del Omar (1904-1982). The collected works of José Val del Omar have been fully remastered for this important digital publication. Extras include numerous photos and essays by Omar that complement his moving image work. Also included is a 44 page bi-lingual printed booklet, in Spanish and English, with an introductory article by Gonzalo Sáenz de Buruaga, detailed credits for each of the films, and comments from the contributing filmmakers.

José Val del Omar has often been considered an essential figure of Spanish experimental cinema. However, Val del Omar can be seen as a key figure of international experimental cinema. This is not a minor point, as displacing Val del Omar from a narrow national narrative is a chance to relocate him within an international constellation of referents. He is part of a global history of images and sounds, connecting his works with some key episodes of the history of cinema. He is the bridge between the 1920s avant-garde and the new underground filmmaking of the 1960s.

P.L.A.T. (PICTO-LUMINIC-AUDIO-TACTILE) ESSAYS

Val del Omar believed in a total cinema where the viewer was completely involved in the film and which touched all the senses, a kind of tactile vision, an aspect of ”pure cinema” of the French avant-gardists of the 1920s. When Val del Omar was in Paris in 1921, he was greatly impressed by the milieu of the Parisian avant-garde (CINÉMA DADA), where cinema was discussed as a sensory experience. Some of these ideas were born out of the French impressionist cinema that he discovered in Paris in the early 1920s (particularly thanks to Marcel L’Herbier). Just as Germaine Dulac envisioned a “pure cinema” based solely on movement and rhythm, Val del Omar understood cinema as a non-narrative cinematographic experience composed of both visuals and sound.

In the 1930s he was back in Spain, working as a cinematographer, projectionist, and photographer for the “Pedagogical Missions” sponsored by the liberal Spanish Second Republic. This State project aimed to bring culture, and particularly cinema and photography, to rural areas. The Misiones Pedagógicas, made him realize the potential of film to be used as an instrument to spiritually elevate and improve people’s lives, a kind of mysticism, inspired by the Spanish Baroque architectural style. Val del Omar’s works within the Missions already saw his first technical inventions, such as the zoom. He believed in the immense power of film to create unity between all individuals by means of a spiritual ecstasy, a kind of mysticism.

Two images from Val del Omar's FUEGO EN CASTILLA (1958-60)

Over the course of his career, he experimented with various immersive cinema techniques that presaged the development of stereophonic sound, wide-screen processes, 3D, and expanded cinema. During the last years of his life, after the death of his wife, he becomes practically an ascetic. In Madrid he moves to a basement where he builds PLAT: Pictórico-Lumínico- Audio-Tactil, in other words, his lab, the place to put into practice all his filmmaking experiments.

He applied such technical developments in his masterwork ELEMENTARY TRIPTYCH OF SPAIN. Shot between 1953 and the mid-1960s, this film is without a doubt the most ambitious project in Spanish cinema history and one referred to by Amos Vogel in Film as a Subversive Art as “an explosive, cruel work of the deepest passion... nameless terror and anxiety...one of the great unknown works of world cinema.” The triptych is a series of three "elementales" (the name would translate as "elementary"), which Val del Omar proposed as a cinematic genre distinct from the documentary. Parts of the triptych won awards at the Cannes, Bilbao, and Melbourne film festivals in the late '50s and early '60s before disappearing from view for decades.

AGUAESPEJO GRANADINO (1953-55) — JOSÉ VAL DEL OMAR

AGUASPEJO GRANADINO (1953-1955), with the primary power of its fountains and the immortal aura of the Alhambra, demonstrated two inventions that produced enveloping experiences: a system of lenses by means of which the film goes beyond the screen to colonize the entire projection room and the peripheral vision of the spectator, and Diaphonic Sound, a particular system of binaural stereo divided into one channel for the scene’s natural sound (flowing from the screen) and another for a soundtrack aimed at the viewer’s psyche, rumbling from the back of the projection room to maximize the all-encompassing experience. Both techniques were devised in the forties and fifties, years before Gene Youngblood wrote his foundational Expanded Cinema, or another total scientist-visionary-filmmaker, Stan Vanderbeek, unknowingly a kindred spirit of Val del Omar in more ways than one, began his activity.

Val del Omar’s persistent exploration of the sensory potential of cinema would also connect him to the American experimental avant-garde of the 1960s and 1970s, and filmmakers such as Stan Brakhage, Maya Deren and Marie Menken. For example, Val del Omar’s ELEMENTARY TRYPTIC OF SPAIN includes the use of black and white negative reversal (Peter Kubelka), as well as the oscillation of light and darkness, of presence and absence (Tony Conrad and Paul Sharits).

ACARIÑO GALAICO (DE BARRO) (1961, 1981-82, 1995) — JOSÉ VAL DEL OMAR

This boxed set also features a selection of films inspired by Val del Omar. They include Eugeni Bonet's experimental feature THROW YOUR WATCH TO THE WATER (2004), which employs Val del Omar's spectacular late color footage, forming a meditation on time and the landscape of Andalusia, as well as VAL DEL OMAR LABORATORY, a 2010 video made by Javier Viver that documents Val del Omar's technological innovations with extensive footage filmed in his still-existing workshop. The closing sentence of all of Val del Omar’s films, reads “sin fin,” or “without end,” instead of “the end,” underscoring a life that is perpetually dedicated to cinematographic experimentation and invention.